The Story of the Corona-Warn-App

Germany was among the first countries worldwide to launch a privacy-preserving COVID-19 exposure notification app, the Corona-Warn-App (CWA). Originally pioneered by a visionary team of volunteer scientists, the concept of using Bluetooth beacons for anonymous contact logging was quickly adopted by Apple and Google, and culminated in an agile government software project of unprecedented speed and scale.

In my role as “nerd in chief” at the Ministry of Health’s digital task force, I was part of the various teams driving this, from the initial scientific vision through the official launch and beyond. At rC3, the 2020 version of Europe’s largest hacker conference, I told the story of how CWA came to be and what motivated key decisions.

Here is the talk in full (in German; English subtitles TBA). The following is a summary of the talk, mainly for international audiences.

Success

The app’s success has far exceeded my own expectations. Some of my favorite milestones so far:

- The app was downloaded in its first week more than any other app, beating Pokémon Go’s previous record

- At the time of the talk (27 Dec 2020), the app had been downloaded 25M times. Under optimistic assumptions, this suggests that around 25% of Germans have used the app

- At the time of the talk, 2600 newly infected citizens anonymously warned their contacts of a potential risk every day. In the mission to stop chains of transmission, those warnings represent vastly accelerated processes and the promise to protect many more people from contracting COVID-19

- The app’s extremely privacy-conscious design allowed me to survive unscathed a live Q&A at the notoriously data-protective CCC hacker conference 😏

While there is room to grow, particularly around the ease and convenience of triggering a warning, and despite technical limitations of the fundamental Bluetooth-concept, it seems likely that the Corona-Warn-App had a net positive effect on the German response to COVID-19 – although it remains to be seen if the effect size can be quantified.

More Than Just an App

One key message of my talk is that, unlike much media commentary had suggested, building CWA was vastly more complex than “building an app” implies. A few highlights include the following.

Scientific Proof-of-Concept

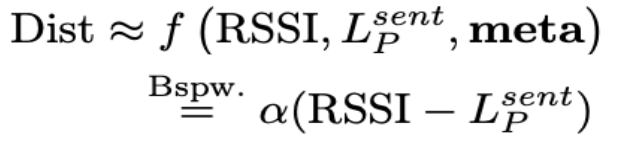

The original idea to use Bluetooth signal strength as an indicator of distance between two phones, and by extension two people, needed to be developed, validated, and calibrated across different phones. The boilerplate formula above shows that by contrasting receiver signal strength (RSSI) with the sender power, potentially under consideration of metadata such as the model of the phone, a distance is approximated.

The original idea to use Bluetooth signal strength as an indicator of distance between two phones, and by extension two people, needed to be developed, validated, and calibrated across different phones. The boilerplate formula above shows that by contrasting receiver signal strength (RSSI) with the sender power, potentially under consideration of metadata such as the model of the phone, a distance is approximated.

This basic idea is fallible to attenuating factors, for example when a phone is carried in a purse that blocks the Bluetooth signal. It is also not robust to behavioral factors, for example whether or not people are wearing masks. It was therefore clear from the beginning that CWA would never replace good old-fashioned contact tracing through health authorities – but using the app promised much-accelerated, albeit uncertain, warnings even of strangers and in chaotic COVID-hotspots.

Privacy

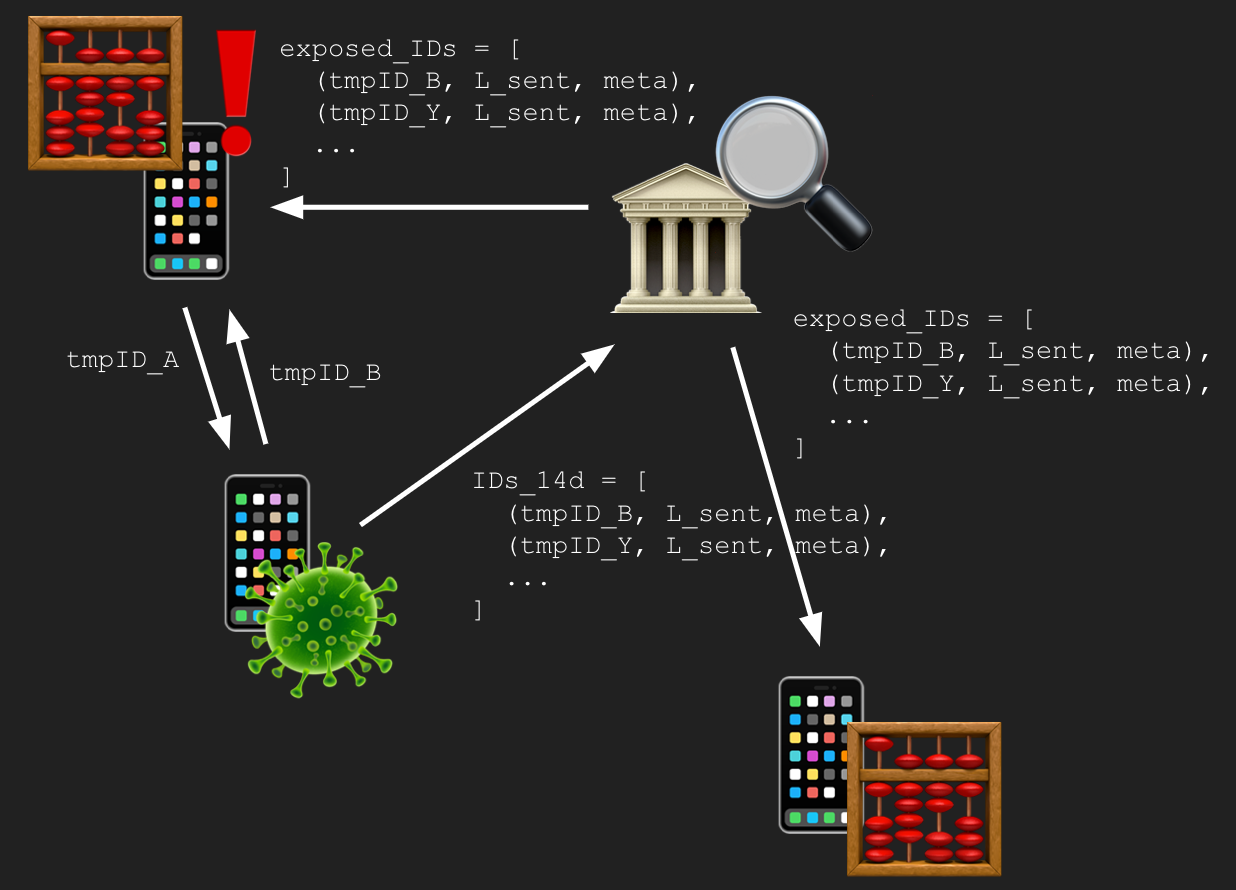

Given the proof-of-concept for distance measurements, an overall system design was necessary. I recount the entire story in my talk, but there was an outright flame war over “centralized” and “decentralized” systems. In order to engender trust from citizens, Germany eventually adopted a decentralized approach, shown below. This was not an obvious choice: potential risks to privacy of contacts needed to be weighed against epidemiological degrees of freedom. For a brief moment in 2020, this was hotly debated between European governments, Apple/Google, and in mainstream media. Ultimately, a constructive and multilateral cooperation between governments and Silicon Valley came to fruition.

In this “decentralized” design, no central server ever learns about contacts, i.e. which phones were near each other. To allow for this, the server distributes the anonymous IDs of all infection-warners to all connected phones, which then determine whether or not they had risky contacts. Amongst other benefits, this means that a potential hacker has little to gain from breaking into the central server. However, it also means that no data is collected on how many warnings were triggered, what types of contact were most common, etc.

Abuse of Anonymity

After establishing how to measure distance and trace risky exposures in a pragmatic and privacy-preserving way, a last step was gate-keeping of the triggered warnings: since the entire system is anonymous, we needed a way to prevent attackers from abusing the new infrastructure by triggering false warnings.

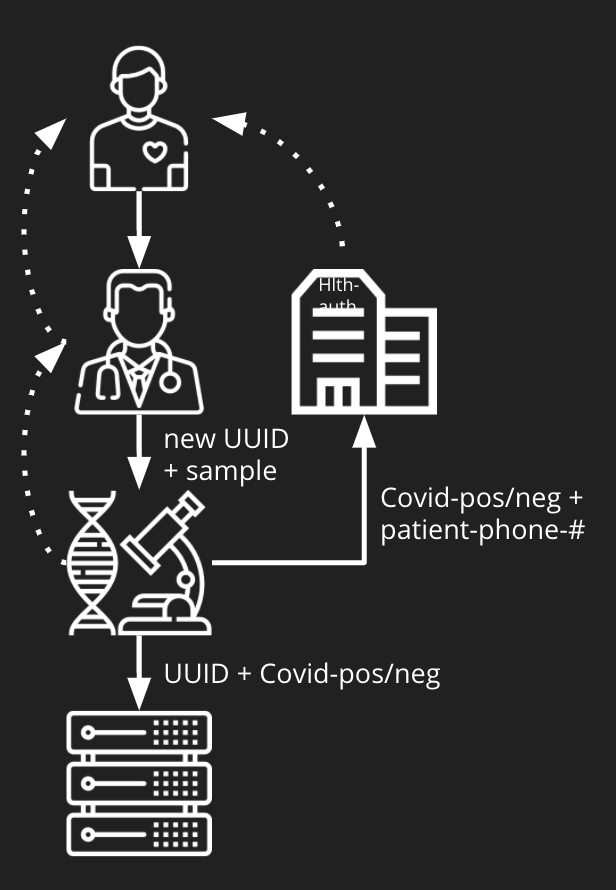

Since the anonymity of the app had to be preserved, since adding workload on the already overstretched public health authorities was out of the question, and since labs in Germany are private and heterogeneous, this was no simple feat. Ultimately, Germany updated its standard form on which Doctors order lab work to include a random UUID for use as a shared secret between the patient and their lab. Using this secret, citizens can now be notified of their COVID-19 lab results through the CWA without needing to reveal their identity. After receiving such a notification, users can then choose to trigger a verified warning to past contacts.

The App

Finally, nationwide communication and PSAs needed to be prepared, support call centers needed to be ramped up, and an open source project of considerable public attention needed to be managed. Oh, and we built an app!

For the entire story, hopefully told more entertainingly, and for my answers in the live Q&A, please refer to the full talk.